[fusion_builder_container hundred_percent=”no” equal_height_columns=”no” menu_anchor=”” hide_on_mobile=”small-visibility,medium-visibility,large-visibility” class=”” id=”” background_color=”” background_image=”” background_position=”center center” background_repeat=”no-repeat” fade=”no” background_parallax=”none” parallax_speed=”0.3″ video_mp4=”” video_webm=”” video_ogv=”” video_url=”” video_aspect_ratio=”16:9″ video_loop=”yes” video_mute=”yes” overlay_color=”” video_preview_image=”” border_color=”” border_style=”solid” padding_top=”” padding_bottom=”” padding_left=”” padding_right=”” type=”flex”][fusion_builder_row][fusion_builder_column type=”1_1″ layout=”1_1″ background_position=”left top” background_color=”” border_color=”” border_style=”solid” border_position=”all” spacing=”yes” background_image=”” background_repeat=”no-repeat” padding_top=”” padding_right=”” padding_bottom=”” padding_left=”” margin_top=”0px” margin_bottom=”0px” class=”” id=”” animation_type=”” animation_speed=”0.3″ animation_direction=”left” hide_on_mobile=”small-visibility,medium-visibility,large-visibility” center_content=”no” last=”true” min_height=”” hover_type=”none” link=”” border_sizes_top=”” border_sizes_bottom=”” border_sizes_left=”” border_sizes_right=”” first=”true”][fusion_text]

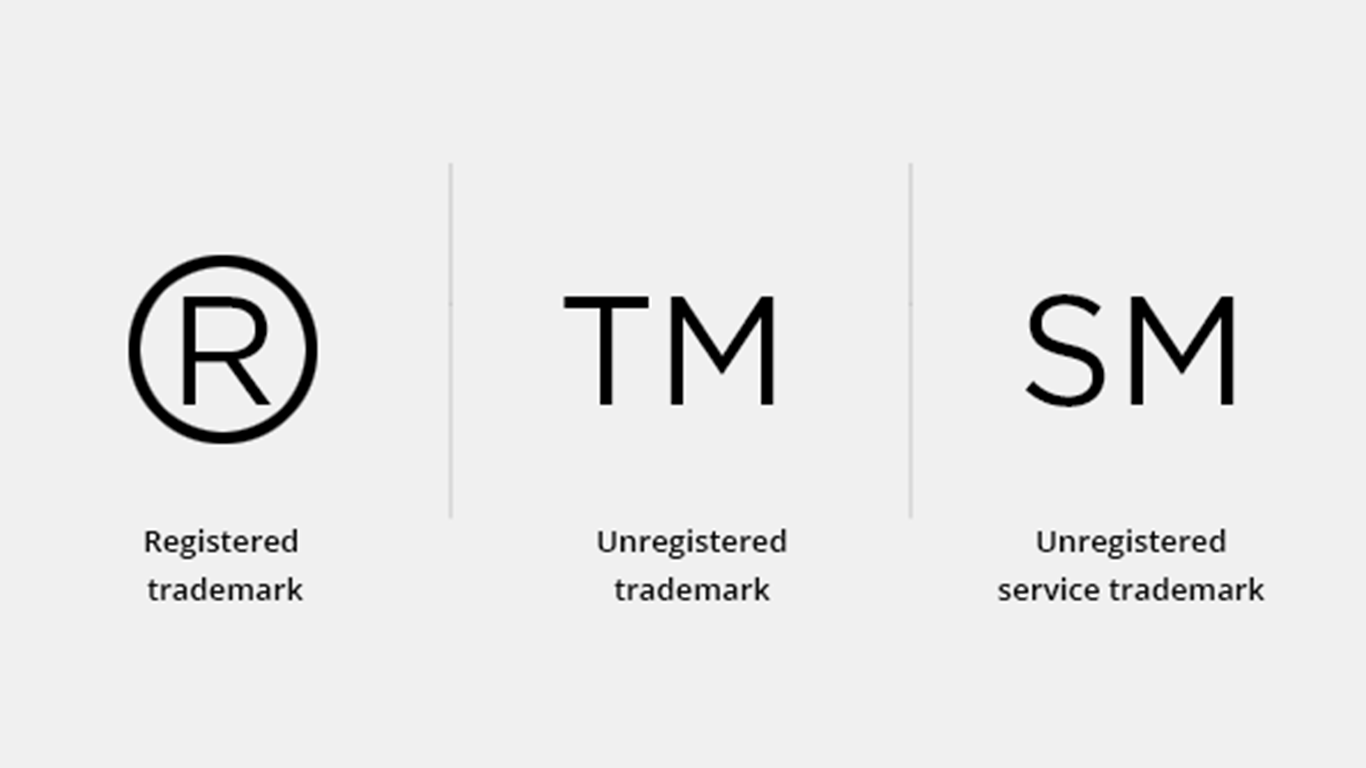

Trademarks are primarily words, logos, or combinations of both that are used to distinguish your goods and services from those of others. Federal trademark registration helps prove your ownership of the trademark and can prevent competitors from around the country from using confusingly similar trademarks. Consider these guidelines in choosing your trademark.

1. Select a word or logo that is not descriptive of your goods or services. Made up words, such as Xerox and Exxon, are the strongest trademarks. The next strongest are real words (such as foods, plants or animals) that have nothing to do with the goods or services; one example is Apple for computers. Marks that simply describe the goods or services, such as Shoes for selling shoes, are not registerable and should not be used. Trademarks generally operate as adjectives, not nouns, so that a trademark owner will say it makes “Xerox laser printers,” not “Xeroxes.”

2. Try to avoid using common terms. You want to select a trademark that will help you stand out and using common terms in your trademark, such as Best or American, are less memorable.

3. Do not use surnames, such as Jones or Smith, in your trademark, because they are generally not registerable. This is especially true where the rest of the mark is descriptive, such as Smith’s Shoes to sell shoes.

4. Do not use geographic locations, such as Italy, in your trademark because they are generally not registerable.

5. Avoid short acronyms and numbers. While there are a few well known acronyms, such as IBM, they are usually hard for people to remember. It will also be very hard to get a .com domain name for a three or four letter acronym.

6. Once you have selected a trademark, check to see if similar words or logos have already been registered (you can check http://tmsearch.uspto.gov to search federal registrations) or are already being used in the marketplace (you can search Google) for similar goods. Remember to also search for slightly different spellings. You cannot register a trademark that is confusingly similar to an already registered mark and there are risks of using a trademark that is confusingly similar to others already in the marketplace. Just because something is spelled different doesn’t mean it’s ok to use it. Whether something is confusing is determined by the “sight, sound, meaning” test.

If no confusingly similar marks are found, then check to see if domain names are available for your mark.

For more information about selecting a good trademark, please contact the offices of Karish & Bjorgum at (213) 785-8070.

[/fusion_text][/fusion_builder_column][/fusion_builder_row][/fusion_builder_container]